Did you know bee hummingbirds weigh less than a dime? It’s a fascinating fact, but how exactly do we know that?

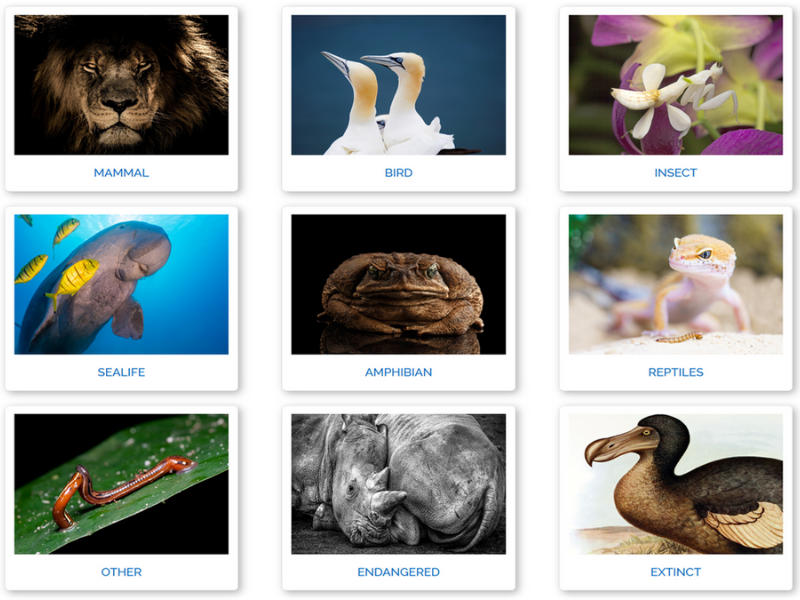

Certainly, there are many things we can know about birds based on observation alone. Observing that birds are less responsive to alarm calls (fellow birds warning about danger) when exposed to traffic noise, for example.

But deeper analyses require more thorough details. Birds are less responsive to human noise. How is noise affecting their stress hormones or a male’s ability to maintain paternity in his nest (i.e., keep the female from “cheating” on him)? Is their body condition affected as a result?

Answering these types of questions requires physical fitness measurements, feather samples, and blood samples. In short, we need to catch the birds.

Anyone who’s ever chased gulls across the beach knows this is a tall order. So how exactly do we ornithologists do so? And what do we do once we have them?

Multiple capture methods exist, each aimed at a species’ behavior (it would be useless to set a trap in the water for turkeys). These methods range from walk-in traps to drop nets to snares. One of the most common in trapping songbirds—species like cardinals and robins—are mistnets.

What is a mistnet?

A mistnet is a large net of nylon rope about 12’ long by 6’ tall. When stretched out between two poles the net becomes nearly invisible—any ornithologist has walked straight into a net at least once. Essentially, it is a large spiderweb. The nets have “pockets” that extend horizontally like layers on a cake. The birds crash into the net, fall into a pocket and get tangled (birds remain unharmed and teams are diligent about checking nets to limit the amount of time birds stay trapped).

Setting up the Nets

Birds are intelligent. They are also excellent at last-minute flight aerobics, pivoting away one inch before crashing into the net. Thus, the positioning and set-up of the net needs to be strategic.

Nets are set up perpendicular to the sun because they lose their invisibility in direct light. The positioning of the net also depends on the target species. Do they fly above the tree line or close to the ground? Are they more likely to be in the grass or among the trees? Oftentimes, ornithologists will scout the area the day before to identify areas of high activity.

Furthermore, the set-up is executed in the dark. If the nets are set up after sunrise, birds are likely to take note of the strange human activity and avoid the area. Furthermore, birds are more active at dawn. Thus, the probability of catching them is higher if the net is set up before then.

Catching Birds

Once the nets are set up, it becomes a waiting game. The team retreats to the base—this can range from the bed of a pickup truck to a flat rock to a cabin—and focuses on waking up, taking turns checking nets periodically. Eventually, the atmosphere becomes livelier, and it is in these moments that my whale joke makes its appearance.

The tranquil atmosphere is flipped on its head when a bird is caught. Often, multiple birds are caught at a time and the whole team is called to the nets. This creates a day of long lulls broken by instances of high activity.

Common Measurements

Measurements vary based on the research question, but some of the more common ones include: length of beak, length of tarsus bone, tail length, wing length, weight. These measurements are associated with avian body condition. Whenever possible, age and sex are calculated—some species have notable plumage differences based on age/sex, while with others it’s impossible to tell without genetic testing.

A blood sample might be taken for studies on genetics, hormones, or diseases. This is similar to getting your blood drawn. In some cases, a bird is taken as a specimen.

Banding

One of the most useful practices when studying birds is banding. A metal band is placed on a bird’s leg like a bracelet. Each band has a unique number. If a bird is caught again—even if by a different ornithologist in a different country—its data can be compared across timepoints. This is especially impactful in migratory birds. How are birds faring in their wintering versus breeding sites?

Color bands are used when one wants to identify an individual bird by sight. How much time is one specific bird spending in different parts of its territory? Color bands are put on birds in different color combinations. Thus, each bird in the area will be uniquely identifiable.

In conclusion, mist nets are useful tools that allow ornithologists to gather information about birds that would be impossible without having them in hand. It requires very early wake-up times and often inclement weather, but the data gathered is meaningful and getting to hold a bird in one’s hand makes it all worth it.