- Hugo Santa Cruz is a photographer contributing to a new Netflix documentary about nature and coping with COVID-19.

- A Bolivian currently stuck in Costa Rica due to the pandemic, he has turned his camera lens on the local landscape, which has helped him deal with his separation from family and friends.

- Many hours spent in the rainforest have given him solace and also an idea to aid the rich natural heritage that he is currently documenting.

- Santa Cruz is now a co-founder of the new Center for Biodiversity Restoration Foundation, which will work to restore and connect natural areas in the region.

Call him inspired.

If Biblical Ishmael were banished to the desert, naturalist Hugo Santa Cruz is quarantined to wander in paradise, a paradise in the Costa Rican jungle, that is.

He is in the Central American rainforest along the Paso de Las Lapas Biological Corridor, an area near the Pacific coast that converges with the mountainous foothills of the western dry tropical forest.

Roaming some 370 hectares of ample primary and secondary forests, regenerated forests restored from human damage, plus plantings, ponds, and biodiverse jungle, Santa Cruz is deep in the wilderness, far from home due to the COVID-19 shutdown of travel and normal activities. He is exploring the jungle, studying the animals, photographing, filming, and registering the species he encounters.

Costa Rica hills

Santa Cruz has found a paradise that allows greater depth and originality of observation, a refuge from isolation while in isolation, a perfect place for environmental inspiration. The zone provides food for scarlet macaws and some 350 species of birds.

“I am surrounded by nature in its maximum splendor,” Santa Cruz says. “Here I am studying and experiencing that it is possible to live sustainably.”

He is finding ways to connect with himself with nature and with the world: “The trips to jungles, beaches, deserts, mountains, and rivers, they were replaced by trips to the interior of my being, trying to get to know myself better, reflecting on what is happening to me and what is happening to the world; trying to control the nostalgia and anguish, which invades my thoughts from being so far from the most important people in my life.”

Santa Cruz is keenly aware that the living world is neither static nor cyclical, but rather that it is undergoing perpetual change. Spins, bobs, and blinks in the foliage hide amphibian body shapes. Upon closer inspection, he can see the moist skin of the frogs.

He is close enough to touch nature, to taste it, to feel the jungle, to hear its sounds. In the forest, there are things going on all around him, inexplicable action, tremendous cracklings, and stirrings of nature. He has to be alert to capture the movement and the surprises.

Santa Cruz is finding within himself a clear understanding that we humans live because the animals and the forest live. As a nature and wildlife photographer and videographer, he is documenting his experience and is among experts in different fields contributing to a pilot documentary for Netflix on life, fears, and coping with the pandemic.

White-tipped sicklebill in Costa Rica

“In this nature reserve, which is now my home, I have spent a lot of time completely alone, or at least without human company,” says Santa Cruz. “From one day to the next, from being surrounded by people of different nationalities and listening to several languages at the same time, I started to hear only the trill of the birds, but my presence does not even matter to them.”

Leaves rustle in the wind, a branch snaps, and a bird’s flight is whipped into the air. In the singsongy silence of the jungle, one can almost hear the deep breaths coming from the nostrils of nearby mammals, but the real show is in the air, in the birds and their diversity of size, color, and the complexity of their songs.

Early on, he spotted Baltimore orioles, broad-winged hawks, Baird’s trogons, gray hawks, green kingfishers, least grebes, social flycatchers, rufous-tailed hummingbirds, scarlet-rumped tanagers, white-necked jacobins, and yellow-bellied flycatchers.

Santa Cruz has admired the blues and other iridescent colors of bird feathers up close, seen the refracting light through the minute feather structures that produce color like tiny prisms. The picture of it stays not only in his camera, but in the memory, in the experience, and in his understanding. Of the approximately 10,000 bird species in the world, all are thought to see in color.

The green parrots prevalent in this part of the world have blue structural colors that reflect and refract light, overlaid by yellow on their feathers, it is the blending of those that makes their vibrant green color.

Staring at leopard frogs on the ground, Santa Cruz’s camera has also captured on the trees red-eyed leaf frogs, cascade glass frogs, pug-nosed tree frogs, and hourglass tree frogs with the golden hourglass on their backs and inflated throats that amplify the sound of air rushing across their vocal cords.

Glass frog in Costa Rica

A yellow pit viper curled among the leaves on a branch, and his camera went ‘click.’ A blue-tailed damselfly. Click. A pink lotus flower. Click. An iguana by the pond. Click. Weightless flight. Click. A scarlet macaw. Silence. Breath held. The photographs focus on everything.

Yet despite being in a kind of ‘Garden of Eden,’ he says, “Sometimes it is just a prison where I have to fight with my fears anyway,” said Santa Cruz, collapsing into a classic split between body and mind.

“I am from Bolivia but life circumstances brought me to Costa Rica some time ago, where I cannot leave now, I am trapped thousands of kilometers from home,” he explains.

“Fortunately, I have a wonderful refuge, a small paradise in the middle of the Central American tropical forest. I am surrounded by nature in its maximum splendor, and I am fortunate to have the help of wonderful people with the Center for Biodiversity Restoration Foundation and the Macaw Wildlife Sanctuary* who make me feel very privileged in these difficult times for everyone.”

He has been able to focus on the diverse range, strength and movement of various animals and has been working on creating corridors of connectivity so that animals can be in their wild environments. Along the way, his study now ranges across an impressive number of forms and an array of functions. He is making conservation models to restore animals and plants to their natural habitats and environmental systems that reflect the diverse adaptations in the area.

But even with the voices of fauna and flora all around, an invisible hand reorders, controls, and reaches across our world: COVID-19.

Golden hooded tanager in Costa Rica

“Knowing that microscopic living beings are capable of causing so much panic and instability in almost all societies in the world, and realizing our vulnerability as a species and our illusory control indicates that the human being is not all-powerful,” says Santa Cruz.

“It tells us that nature is not here for us, and that if we want to survive we will have to learn to live in harmony with it because we are only a tiny part of it,” he said.

In this cauldron, “The Center for Biodiversity Restoration foundation was born with the idea of expanding the landscape restoration work outside the Macaw Sanctuary,” explained Santa Cruz. “This area that was once a deforested area, with poor and compacted soils, today it is a small Garden of Eden brimming with life, everything.”

Biological diversity is related to the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat, said Santa Cruz, thus the importance of biodiversity restoration. “The levels at which biodiversity is comprised are different; from genes, followed by species, communities, ecosystems, and finally landscapes; where life interacts with its physical environment.”

As the coronavirus crisis continued, Santa Cruz found meaning in his escape.

“We want this existing model to expand over the biological corridor which includes the sanctuary,” said Santa Cruz thanking the efforts of the land’s owners “who managed to regenerate the ecosystem with the help of reforestation, agroforestry, and ecotourism.”

He said his dream is to create an international exchange for ideas that would draw from the successful Costa Rican experience to allow people from Bolivia and other Latin American countries with environmental problems to share experiences and develop solutions.

The northern jacana in Costa Rica

“We plan to open a biological station that will serve as an environmental school and experimentation center for people interested in contributing to conservation, whether local or even from other countries,” said Santa Cruz.

This biological station would ideally direct the environmental projects of the biological corridor, he said.

Perhaps, thinks Santa Cruz, in this shelter from the COVID storm he has found, a door for a rebirth and a reconnection between humanity and nature will be opened.

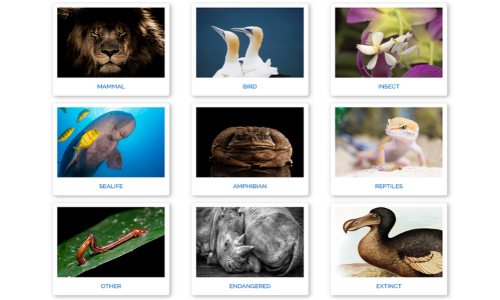

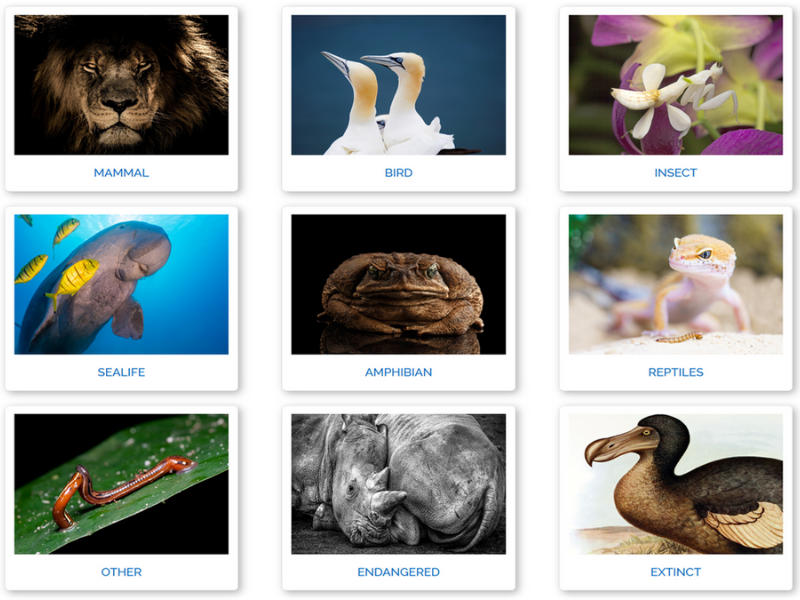

* Here’s a video that Santa Cruz shot in the Macaw Sanctuary, a private protected area within the Paso de las Lapas Biological Corridor, showing the many kinds of animals found there, from birds to insects:

The article was originally published by Mongabay by author Erik Hoffner and can be found here.